The Mad Scientist: SouthYeast Labs and Carolina Bauernhaus

LIQUID ASSETS

SouthYeast Labs and Carolina Bauernhaus

Wild yeasts are everywhere. When David Thornton and Even Skjervold conceived of a lab built on isolating and reproducing these yeasts, the picture of local beer changed forever.

South Carolina is a foodie destination, but the only alcoholic beverage we’re truly known for comes in a Mason jar with as many variations as Grandma’s biscuits. Beer enthusiasts flock to try regional brews like Central Bohemian pilsners, long-handled pulls from cellared English pub casks, or the hard-to-get Belgian Trappist Westvleteren XII. The US craft brew scene has exploded with delicious artisan beers, but most imitate European styles using imported European yeasts. SouthYeast Labs and Carolina Bauernhaus Ales, both located in Anderson, SC, think it is time for the south to develop its own beer styles with wild yeasts from this area.

SouthYeast Labs was created by business partners David Thornton and Even Skjervold. The pair met in Thornton’s “Science of Beer” class at Clemson University and discovered a shared fascination with the prevalence of local yeasts. It turns out there are infinite sources of area flowers, fruit and even honeybee hives where yeasts can be harvested and tested for beer-worthiness. Though the company is still under construction in many ways, they have already put together a catalog of 22 local yeast varieties that are currently being utilized by more than 30 commercial regional breweries, such as in Brewery 85’s crowd-pleasing (864) Weizen.

Even though Louis Pasteur didn’t prove that alcohol was fermented by yeast until 1857, the celebrated brewing techniques for European beers have centuries of history based on local climate, terrain, ingredients and regionally-specific yeast strains. These days you can mail-order yeast labeled “Bavarian Lager 2206” or “French Saison 3711” but historically, brewers passed down starters (just like with sourdough breads) to produce their favorite drinks. The properties and flavors a local yeast imparted would heavily influence a brewer’s decisions for how to best complement and perfect their craft. Over time, each region became known for the resulting masterpiece.

To beer fans focusing on tasting hops, wheat, barley, oats, malt, fruit, spices and even the water quality that goes into a brew, the yeast may seem like the least significant part of the process. It turns out that many of the flavor notes described by beer judges—butterscotch, cloves, bananas, green apple, cherries—are actually chemical compounds created by the yeast during fermentation. A beer can contain hints of plums, smoke or strawberries without ever having encountered these ingredients, if the right yeast is used.

Like any good invention, finding the best yeasts for the job requires patient experimentation.

“Once we isolate a variety of yeast, we put it through beer boot camp,” David said.

To graduate, yeasts need to be able to survive up to 10% alcohol, a 4.5 pH, as well as flocculate, or settle into visible layers so they can be filtered out of the final product. (Now go impress someone by using the word “flocculate”). The amount a yeast flocculates determines how clear or cloudy a beer will look. Yeasts that pass these initial tests are bred in a wort and tested in various beer recipes. The yeasts that produce the best results are propagated for sale.

Beer means it’s party time—for microbes. The 1500 or so species in the yeast family are all single-celled fungal organisms that convert carbohydrates into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Most beers and wines are made using the same species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, though other species are sometimes used.

But beer yeasts have great varietal diversity, both bred and in the wild. This is similar to apples and oranges. If all the apples we have ever eaten are the species Malus domestica, then the sexually unique seedlings of that species are given varietal names to distinguish them from each other such as ‘Granny Smith,’ ‘McIntosh,’ or ‘Arkansas Black.’ Like human babies, every seed from a plant is encoded with its own set of genetics derived from its parents; if I found an apple tree that grew from a seed someone threw on the ground, I could collect cuttings to name however I like. When SouthYeast Labs finds a wild yeast that tastes good, they name it like it is a feral apple and distribute it as a unique variety.

Many of the yeasts in their catalog were originally collected from Clemson University agricultural testing areas. David and Even utilize the “control” plots for a crop like peaches—these are the comparison plants in Clemson’s scientific trials that are not sprayed or treated in any way. Fungicides kill yeasts as well as their intended pathogens.

“Once we had the yeast, we needed brewers willing to do beta tests. That’s how Carolina Bauernhaus was born,” David said.

Keston Helfrich met David at a meeting of the Upstate Brewtopians, a local homebrew club, over a powerful batch of David’s distilled beer. (The looks they exchanged when it was mentioned made me jealous I wasn’t there.) Keston had brought an ESB (Extra Special Bitter, an English beer style) made with American hops, which impressed David. Both David and Keston were attracted to homebrews that were daring and heavy on experimentation, which led to Keston becoming one of the SouthYeast Labs beta testers.

“He was already brewing the kind of beers I’d hoped for; he likes to play with the styles and techniques that fit these yeasts,” David said.

At first David just wanted to make sure his yeasts were a product local breweries would want, but after taking samples of Keston’s beers to a presentation for the American Society of Brewing Chemists, the plan changed to include the brewery.

“Lots of major brewers were telling us to make Keston’s beers available to the public,” David said.

The result was Carolina Bauernhaus Ales, with Keston as the head brewer. David describes it as a nanobrewery, even smaller than a microbrewery.

“I’ve brewed all my beers exclusively with SouthYeast Labs wild yeasts since I first tried them in 2012. They just get the results I want,” Keston said.

Playing with beer recipes and introducing people to unusual beers is his dream job.

“I mean, who wouldn’t rather do this than stare at a computer all day? I love watching people’s reactions even more than drinking it myself. Any reaction fascinates me, whether they love it or hate it.” He mouth quirked at the edges as he added, “Hopefully, they love it!”

Ask Keston about how he pursues and tweaks his recipes, and the human origin of regional beers becomes immediately apparent. It’s easy to imagine him behind the weathered counter of an ancient pub-house while proudly serving his specialties to blacksmiths, cobblers, tinkers, and perhaps a few hobbits. He enthusiastically describes favorite batches, such as a nutty brown fig ale with caramel, malty tones, faster than I can write them down.

“Wild yeast just rips through the sugars and leaves a very dry beer. A lot of the results are more like wine and I’m finding even people who don’t think they like beer love those,” Keston said.

“I love brewing light, clean beers that are refreshing to drink when it’s hot. This is not the climate for Russian beers; when it’s 97 degrees, do I want to drink a big, thick, syrupy beer? We have what, 2 months out of the year for that?”

Keston is from the North Carolina mountains, Even is from Norway, and David is from northern Virginia. Both Keston and David are quick to say they fell in love with the Upstate for its lack of snow. They also feel summer brewing styles are the best showcase for wild yeasts.

“Most of the beers are lighter but I am working on a stout, plus a Belgian-inspired strong, dark beer that came out with a big hit of rye and notes of rich fruits like plum and cherry. It’s all from the yeast, there is no fruit in the recipe,” Keston says. He adds that it takes well to aging in wooden spirit barrels, which they get locally from places like Six & Twenty Distillery in Piedmont and Dark Corner Distillery in Greenville.

“We do more fermentation in barrels than in stainless steel vats, which is atypical,” David said.

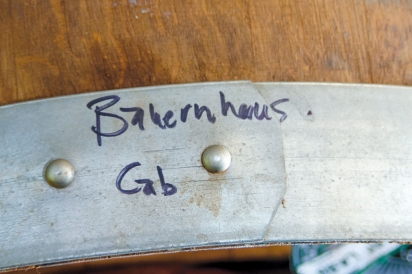

Most of the barrels they obtain from distilleries are made of oak and have the lingering flavors from spirits like whiskey, apple brandy, port, sherry, and muscadine fortified wine. Each acquired barrel goes through a succession of use in the brewery. The first batch to be aged in a new barrel is chosen to take advantage of flavors the former spirit will impart. After that, the barrel is considered “neutral” and can be used for any of the brewery’s beers. Barrels that show signs of leaking can be “swelled” by filling them with boiling water to expand and merge the wooden rings. Water and activated charcoal are used to clean them and remove off flavors between batches. Once the barrels deteriorate beyond use, they’re composted.

“We’re using barrels because the porous wood soaks beer in when warm and spits it back out when cool. This process gives flavor to the beer while filtering and maturing it. The flavors are much more mellow and nuanced,” David said.

The barrels are tested regularly for any contaminants.

“Since we’re also a laboratory, we don’t have to send out our samples. We can immediately find out if there is something going wrong. The main thing we want to avoid is Acetobacterium, which produces vinegar,” David said.

Right now, the “lab” is David’s living room. Carolina Bauernhaus Ales isn’t technically open and SouthYeast Labs is incubating for breweries from a space where most people keep comfy couches and a TV. However, both companies are well on their way to being fully-realized. They hope the doors to the taproom will be open by the end of 2015 with beer available in stores before then. The brewery building will also be used to house SouthYeast Labs until it can find a permanent home.

“SouthYeast started first and at some point Carolina Bauernhaus leapfrogged it in funding. Now we’re using the brewery to incubate the yeast business,” David said.

Then he pauses with a smirk, “Get it? ‘Incubation’ is how you grow yeast!”

SouthYeast Labs got its first break when Even began the MBAe (Master of Business Administration in Entrepreneurship and Innovation) graduate program at Clemson. Through that, he entered and won the CertusBank EnterPrize top award of $20,000 for his presentation on SouthYeast Labs. In addition to presenting their business plan, the judges were served a beer sample, whiskey sample, and biscuits all fermented with wild yeasts they’d collected.

“I helped, but Even was the show pony– I just made biscuits,” David said.

The pair used the money to buy stainless steel kettles, an industrial boiler, and other sterilizing and growing equipment for their lab.

“We’re at max capacity until we can expand out of my house, I can’t take additional clients right now,” David said.

In order to continue growing, both companies held a variety of fundraisers. Separate crowdfunding campaigns (a public fundraising technique that allows people to contribute money online for amount-based incentives) were established for both SouthYeast Labs and Carolina Bauernhaus Ales. A donor who gives ten dollars might receive a bumper sticker whereas a donor of 50 dollars receives a t-shirt with the company logo–the perks are usually relevant to the cause. In this case, brewery swag was particularly tempting to community investors.

“We offered stuff like flight glasses and growlers all the way up to things like private tasting parties at the finished taproom. A local attorney bought that one to treat his clients,” David said.

Another fundraiser involved their own version of a CSA— in this case community supported ales instead of agriculture. With a traditional CSA, people buy shares from a farmer at the beginning of the season and receive baskets of produce as it comes in. In this case, the CSA shares went into brewing some special southern wild yeast beers, packaged in large bottles with an attractive indie label. David says participants received two bottles of each variety, one for drinking and one for cellaring.

“We also did a food truck rodeo—not a real rodeo but the food trucks are corralled in the center and there is live music and of course beer. Plus we did a baking event where a local chef used our yeast to bake breads and desserts,” David said.

The end result is a group of patrons who will feel a sense of ownership when they walk through the door. Each barstool, tap handle, and bunghole cork has been sponsored by a member of the community.

The brewery and taproom will actually be separated, for aesthetic and practical reasons, by a wall of wooden barrels that already stretches across the center of a downtown Anderson, building that was formerly used as a family-run mechanics shop.

“Everything will happen in the same place, and there will be a viewing window between the taproom and brewery so you can see the Oompah Loompahs at work,” David said.

Visitors to the taproom will be able to order a flight (a sampler tray of 4 miniature beers), full pints, book private parties, listen to frequent live music, and order appetizers from the bar. If they’d prefer a full meal and get too wobbly-legged to wander next door, neighboring restaurant McGee’s Irish Pub will bring over Celtic dishes like bangers and mash—or keep it southern with some shrimp ‘n’ grits. The menu is extensive enough to have complements for any style of beer.

David hopes to always have a Certified Cicerone on staff to educate patrons about the beer categories they offer. Cicerones currently learn mostly European styles, but they soon may need to add a traditional Carolina style to their repertoire. I can already hear near-fanatical southerners swearing their local beer is the only way to wash down the family’s barbeque recipe.

David explains that their beers are currently inspired by historical Belgian and German styles, but will be more accurately described as American wild ales.

“Our signature line will be what we’re calling our ‘Source Series,’ sort of like a Belgian saison sour, a farmhouse ale. We’ll take a yeast from a fruit to brew with and then recombine the same fruit the yeast was isolated from into the batch. So, a beer brewed with yeast we found on nectarines will have actual nectarines added to the final product,” David said.

One of the yeasts destined for the “Source Series” was harvested from the skin of prickly pear cactus fruits, which when ripe are sweet-tart with the deep red hue of beets.

“That one makes a gorgeous, purple beer that is full of antioxidants,” David said.

Many of the beer ingredients will also be local, especially the flavorings. 90% of Carolina Bauernhaus’s malts already come from Riverbend Malt House in Asheville, NC and David recently purchased 28 acres designated to become a permaculture farm that supplies the brewery. David plans to grow Cascade hops, some grain, nuts and fruit, including uniquely Southern flavorings like pawpaws, pecans and native passionfruit (maypops).

The farm will add additional credibility to the “Bauernhaus” part of the equation. David rattles off the working class German beer styles like Gose, an unfiltered sour ale with a little sea salt, and Berliner-weisse, a sour wheat ale that is considered a lunch beer.

“It was common for farmers to drink this in the middle of the day because there is less alcohol and the beer contains electrolytes from lactobacteria.”

He breaks into another grin, “Really, I’m just trying to justify drinking beer at lunch time.”

Heck, I think I’ll drink one for breakfast. The fruit ones make it okay, right?

SouthYeast Labs

David Thornton and Even Skjervold

www.facebook.com/Southyeast

Carolina Bauernhaus, Keston Helfrich

www.carolinabauernhaus.com