Way Down Yonder in the Pawpaw Patch

Rediscovering America's Largest Native Fruit

Unless you spent some childhood hours singing about Nellie pickin' up pawpaws and puttin' 'em in her pocket, you've probably never heard of North America's largest native fruit. Asimina triloba is usually known as pawpaw in this region, though it also has a plethora of banana-focused common names that give a distant hint of its flavor. Pawpaw fruit can weigh up to two pounds and tastes like a mango, banana, and vanilla custard smoothie. Native Americans spread its southeastern seeds as far north as Canada, Hernando de Soto “discovered” them for the western world in 1541, Thomas Jefferson proudly sent seeds from his Monticello orchard to France, George Washington enjoyed pawpaws chilled before the age of refrigerators, and Lewis and Clark wrote that the nutritious fruits sustained them on their travels. The reason you haven't heard of them? They ship poorly.

Pawpaws confounded fruit breeders with their vulnerable flesh and unique ripening patterns. Who hasn't seen a perfectly ripe bunch of bananas morph overnight into brown-mottled, cloying mush? Pawpaws raise the stakes even higher with their inability to ripen if picked green, their faster fermenting rates, and their delicate, thin skins. If the bananas we buy often have dark bruises under their husky wrappers, imagine them with skin as thin as a pear.

On top of that, pawpaws are finicky about pollination. Although each tree bears male and female flower parts, they aren't known for self-pollination. They are also saprophytic, which means the fragrance of their bat-like blooms is not designed to attract insects like bees and butterflies. Carrion flies and beetles are their target audience, but pawpaws aren't smelly enough. If you shove your nose right into a bloom you might be able to detect the faint scent of roadkill, but our native flies seem mostly unimpressed by it. Growing two or more pawpaw seedlings increases the rate of pollination, but they still might require a gardener to provide sex therapy with a pollen-coated paintbrush. Overall, they don't easily lend themselves to mass production; pawpaws are definitely a fruit for the backyard enthusiast.

Ask a gardener or forager when they first learned about this forgotten treasure and they're likely to remember the moment as vividly as the moon landing or a national tragedy. I encountered my first pawpaw as a teenager, splashed amongst the pages of a flimsy mail order catalog that also offered items like turquoise blue roses and two-story tall potted geraniums. After persuading my mom to place an order, we wrote off the package of plain pink roses and dried out DOA “pawpaw” twigs as evidence the catalog only offered snake oil.

A few years later, I met Chris Sermons when we were both invited to spend the weekend at a friend's cottage in Black Mountain, North Carolina. While our friends behaved like proper 20-somethings—getting drunk in the cabin porch rocking chairs—Chris and I geeked out exploring and identifying all the native plants. The conversation turned to pawpaws, and I was excited (and jealous) to learn Chris had them growing at his family farm. Still, it meant they weren't a myth and my interest in them was rekindled.

Chris is still farming his family's 120 acres as Bio-Way Farms in Ware Shoals. Production really took off in 2004 when his family planted 2,000 asparagus crowns. Chris has continued to experiment with unusual foods like pawpaws, ground nuts (Apios americana), and Egyptian walking onions. On most farms, the annual crops are tilled under at the end of the season, but perennials can't be treated this way since they take time to establish. Chris quickly noticed that it was easier to work with nature than fight against it and began researching alternative ways to manage his farm. In 2010, Chris studied with North Carolina instructors Chuck Marsh and Patricia Allison to become a certified permaculture designer. Permaculture's scientific, whole-systems approach to “permanent agriculture” is perfectly suited to Bio-Way's perennial crops, but also benefits the more traditional annual foods they produce.

Last August, I traveled to Bio-Way Farms for a tour and a peek at Chris's mature pawpaw trees. Chris tells me he purchased his original pawpaws from Woodlanders nursery in 1995 as forage for deer and other wildlife. Only the ripe fruit of the pawpaw is interesting to wildlife, so the young trees don't need to be caged for protection. If mammals (including humans) consume the unripe fruit, seeds, leaves, or stems of pawpaw trees, acetogenins in these parts of the plant cause what can be kindly referred to as gastric distress. Gardeners looking for deer (and even goat) proof plants should consider growing pawpaws, but recognize that the sweet, fallen fruit is fair game for deer, foxes, opossums, and raccoons. The stunning zebra swallowtail butterfly (Eurytides marcellus) will eat the leaves as a caterpillar, but never in quantities that hurt the tree.

Chris says that pawpaws are an excellent tree to use in forest farming, a growing technique that mimics a natural forest ecosystem to reduce work and increase yields. Each organism in a forest garden is chosen for its ability to integrate with other species, providing all the system's needs. For example, pawpaws might be chosen as an understory tree in a planned forest with walnut trees as the taller canopy species. Walnuts produce a natural herbicide called juglone that doesn't affect the pawpaw, making them good companions. This forest section may include other productive deer or goat resistant specimens in the vine, shrub, herb, and mushroom layers. To manage weeds and fertilize, goats could be allowed to graze under the trees on a rotational basis. During the pawpaw's bloom, the goat manure would serve an additional function of attracting the flies needed for the pawpaw's pollination.

Chris's original pawpaws are unimproved wild specimens that produce seedy but delicious fruit. More recently, he also added named varieties that have been selected over the last 25 years by breeder Neil Peterson for uniformly large fruit, fewer seeds, excellent texture, and superb flavor. Peterson's pawpaws are available through nurseries like Edible Landscaping in Virginia and One Green World in Oregon. His varieties bear Native American names like Susquehanna, Potomac, and Shenandoah.

Although pawpaws are starting to show up seasonally at farmers markets in late summer, Chris says his limited harvests are currently only available as an introduction to worthwhile native foods for Bio-Way's CSA shareholders. He enjoys educating customers.

Over tea, Chris is excited to tell me about Bio-Way's forest shiitake log production, ways the farm uses weeds, the plants being grown in the micronursery, and plans for the honeybee apiary. His cabin is spartan and reflects his interests— a simple arrangement of Native American artifacts scavenged from the soil, back issues of Permaculture Activist magazine, agricultural textbooks, field guides, a loyal canine, and an excellent window view. The conversation turns to a forgotten experimental pawpaw orchard from the 1920s and Chris's disappointment that an old trial planting near Washington, DC has been destroyed. Chris says it has taken a while for Americans to notice pawpaws as a native treasure, but people are starting to clue in.

One upstate resident who is no stranger to pawpaws is County Extension agent Danny Howard. Danny has a home orchard that boasts around a dozen mature, improved pawpaw specimens. His trees are salvaged treasures from a phased-out university trial at Clemson with large, improved fruit set. Danny says caring for pawpaws is mostly carefree, though he does hang raw hamburger in the trees to help the flowers attract flies when they appear in mid March through April. He laughs that his wife doesn't object to the rotting meat lures, but she won't let him bring pawpaws in the house. The aroma of a few ripe pawpaws could compete with truck full of cantaloupes sitting in the sun.

After he freezes some pulp (he says to just spoon the flesh into a freezer container, no processing required), he's on a quest to find homes for extra pawpaws. Each year I get a call from Danny telling me to come get the harvest he brought with him to work (his fellow co-workers share his wife's sentiment about the overpowering scent and banish the fruits to the empty conference room). It doesn't really work, since the moment I walk in the office I can just follow my nose to the crate of mottled yellow and tan fruits. In exchange, we provide him with a sample of our annual pawpaw beer.

This year my husband Nathaniel brewed a pawpaw pale ale that utilized five pounds of pawpaw pulp as well as the fresh 'Cascade' hops we grew ourselves. It compares favorably with the delicious pawpaw wheat beer we brewed for our wedding, except that this beer has malty, caramel undertones that go well with the floral pawpaw finish. It's surprisingly smooth for a brew with nearly 8% ABV. The pawpaw causes the color to be a little dark for a pale ale— similar to the deep sunset hues of a pumpkin beer. We also went a little overboard with the priming sugar so the bottles have to be opened with care to avoid a fountain of foam like a cartoonish spray of champagne. As a small batch, we'll mostly drink it on special occasions. Our daughter, Rayna, prefers her pawpaws raw. She selects the nicest fruits and retreats into her bedroom with a spoon before I set to pulping the rest. Pawpaw pulp can be used in any recipe that calls for bananas, mangos or pumpkin puree. One of our favorite uses is as a custard pie enhanced with a touch of vanilla.

During processing, it's a little challenging to scrape the pulp clinging to each seed, but they are easier to put up than most fruits. When perfectly ripe, the skin peels off with little trouble. After I finish, I dump the remaining bowl of seeds into a planting pot and leave it outdoors for the winter to stratify— the seeds need to go through a winter to sprout.

Like other American fruits such as persimmons and passionfruit (Passiflora incarnata), pawpaw seeds will die if allowed to dry out. The dried seeds have their own uses as jewelry or buttons and were once superstitiously used as pocket “touch pieces” in Ohio – thought to promote luck, love, and protection from evil.

If you're looking for a more functional urban tree than a Bradford pear or dogwood, they're an attractive landscaping plant. The large, tropical green leaves turn a rich yellow in the fall, similar to the hue of hickory trees. This also makes the wild colonies easier to spot from a distance in the fall, so foragers can mark the location for future harvests. Pawpaws have a natural tendency to form shrubby thickets. If you want them to have a single trunk, remove any side suckers before they send down their long taproot.

Pawpaws are usually grown eight feet apart, but you can plant two close together if you're short on space Another space-saving technique is espalier, which is a pruning method that shapes the trees into a living fence or wall covering. Young pawpaws start out with a fan pattern that lends itself well to this type of pruning. Though pawpaws can reach 20 feet tall, they can be kept at a size of eight to ten feet. Pawpaws fruit best in full sun but will take some shade.

We delivered some of Danny's pawpaw pulp to Grits and Groceries in Belton. I was particularly interested to see how this ingredient inspired him after reading an interview with a high-end restaurant supplier who said that one out of four New York City chefs hates pawpaws. As a Carolina native himself, chef Joe Trull had no trouble dressing pawpaws up for the gourmet table.

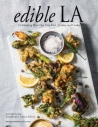

Not that Grits and Groceries has any air of pretension. My GPS tried to overshoot the entrance by half a mile, but there is no missing the giant rooster statue positioned in front of the country diner. Nor the fact that this restaurant is the only business at a rural four-way stop surrounded by pastures and farmhouses. I walked past tables stuffed with lunchtime regulars to order an iced tea at the counter. Joe casually placed two decadent desserts in front of me and began to garnish them with whipped cream and candied cashews— pawpaw key lime pie and a banana split with pawpaw ice cream.

Wow. The fragrance of pawpaw was a perfect counterbalance to the citrus acids in the pie, and the coconut crust with hints of brown sugar was far more interesting than traditional graham crackers. Pawpaws are nearly a custard on their own, but the richness of eggs and cream brought them to a smooth perfection. A draft from the ceiling fan threatened to blow Joe's printed recipes off the counter and I edged the corner of my copy under my glass.

The pawpaw banana split was my favorite. Joe had highlighted the sunny colors of pawpaw as well as its tropical flavor. I couldn't believe I'd never combined pawpaws with chocolate when I tasted my first fudge-sauce soaked bite.

Healthy as well as delicious, studies at Purdue University say pawpaws are good sources of vitamin C, magnesium, iron, copper, manganese, potassium, riboflavin, niacin, calcium, phosphorus, zinc and several essential amino acids. There are also pawpaw compounds being researched for the treatment of prostate and colon cancers. With a nutritional profile like that, I'm surprised I haven't seen pawpaw extract on the health food shelves next to goji berries, maca and chia seeds. Joe mentions that pawpaw is available to order online as frozen pulp. Since pawpaws are naturally soft-textured, the pulp tastes essentially identical to the fresh fruit. If you're interested in trying pawpaw, frozen pulp is your best option other than growing them yourself. Unfortunately, wild patches of pawpaws are usually clonal colonies that rarely set fruit. And if my neighbors were watching in April as I stood on a stepladder straining to reach all our pawpaw blooms with a paintbrush, they may have wondered what I was up to. I think it's worth it. With any luck, by August I'll be picking up pawpaws and putting them in my pocket.

Bio-Way Farm

197 Bio-Way

Ware Shoals

864-992-6987

www.biowayfarm.com