Farm Bureau Family

Upstate native and local business owner considers her family’s rich farming legacy.

In the general country store on Duncan Chapel Road early in the twentieth century, you could find hoop cheese—a simple, traditional cheese made from only cow’s milk—and big cookie jars. I know this because P.O., the store’s owner, was my great grandfather. P.O. was known for extending credit certain times of year in the store until crops were harvested or animals were butchered. He did what you called “putting it on the books,” the books being a spiral notepad or on the wall in the country store. Everything a customer took on credit was logged, and P.O. would scratch through it when customers returned to pay. Some people could afford to pay in cash, but often being paid meant accepting a whole hog or harvested vegetables. “Farm fresh” had a different meaning at this country store, as you could stand on the front porch of the store and touch the farm at the same time.

P.O. was born and lived his entire life in the Ebenezer community near Bowman, South Carolina. He started plowing when he was six years old and never stopped. P.O. operated a dairy farm and a general country store, and raised corn, cotton, wheat, vegetables, and soy beans for commercial production. P.O. never mentioned having slaves, but he did say he raised six boys who worked the family business until they left home.

Everybody else in Ebenezer may have called him P.O., but in our family he’s Pappy Paul. His wife, my great grandmother O’Ressa Way Weathers, was called Mammy Ressie. Their six boys—Pinckney, Pitts, Will, Raymond, Watson, and Leland—were born, spent their entire life, and were buried within a two-mile radius of the farm.

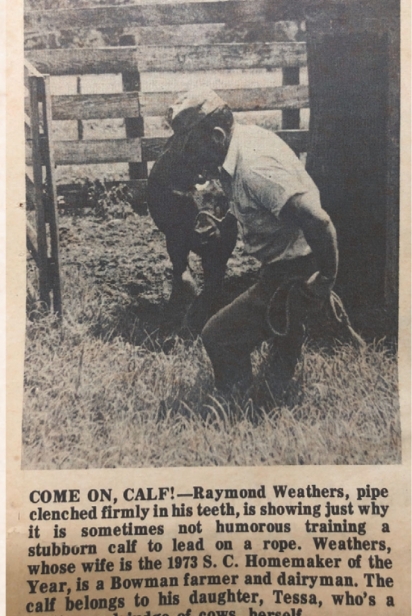

P.O.’s son Raymond, born Raymond Wesley Weathers in 1922, was my grandfather. When he was the age I am now, he bought his first herd of dairy cows—23 Holsteins to be exact. He had been working with his father-in-law, John Edward Easterlin, on his small dairy operation, milking six cows and driving two mules all day for $15 each week. (John Easterlin was the son of David William Easterlin & Anne Augusta Myers Easterlin. David William Easterlin was born in 1849 on Easterling Plantation with 606 acres, 8 slaves, and cotton as the main crop.) Raymond’s brother Pitts was in line to take over Pappy Paul’s farm operation, including the dairy. As a result, Granddad went to work instead for his father-in-law at his dairy four miles north of the family farm. Pappy Johnny’s herd was small and my granddad was looking to grow so he set out to open his own dairy operation, but Pappy Johnny had another idea. He suggested my granddad buy his own cows but come into business with him instead of working for him. My granddad drove to Savannah, Georgia, with no money and bought 23 cows.

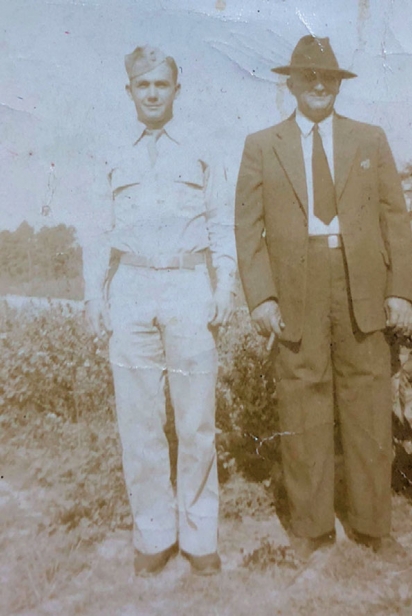

The first time Granddad left home was in 1942 to be a Corporal in the US Air Force, eventually serving in WWII. He was short and slim but muscular with thin, dark hair. He must have never weighed more than 180 pounds. His forearms and hands were dark and leathery, from sun and hard labor. They were tough on the farm and gentle with his family. In this way they told the story of his life. For 25 years, he used his forearms and hands to milk cows before dawn, work all day in the field, and raise a family at night.

As Granddad got older, I would sit with him and listen, writing as I listened. I wrote pages and pages of his stories and memories, not correcting his grammar in my text to salvage his accent. He once told me,

I called Henry West at National Bank and said, ‘I’m down here to a sick cow sale but I don’t have a nickel. Can I buy some cows?’ He told me to buy all I wanted and he would take care of it. If I wanted cows, he say go buy them. He was real good.

Pappy Johnny and my granddad milked registered Holstein cows together from 1950 to 1960. My Uncle John was born in 1950, my mom was born in 1954, and my Aunt Tessa was born in 1958. Like Pappy Paul with a plow at age six, Granddad said my Uncle John came to the dairy to help as soon as he could walk.

When John Owen started to school, as soon as the bus dropped him off he would run to the dairy. I worked in the field; he would work in the dairy. One day, I was in field cuttin’ hay, I saw a man comin’ toward me and I knew something happened to John Owen. When the milk truck came to pick up the milk, John Owen would clean the tank. He didn’t put the cap on and all the milk went down the ditch. Allen was coming to tell me not to fuss at him. I said you tell him to get that much in the morning when he milks!

In 1960, Pappy Johnny said he was finished. My granddad bought him out, but he didn’t have much— most of the cows already belonged to my granddad. In the 1960s, my granddad was in the right place at the right time. He was the sole proprietor of a growing dairy herd in the Dairy Capital of South Carolina and milk was bringing a good price. Hard work was key to profit in the dairy industry and my Uncle John told me they were even more profitable because they did everything themselves.

In 1971, my granddad was President of the Bowman Young Farmer Chapter. During his time as President, the chapter was recognized with the Beaver Award by the committee on Building Our American Communities for outstanding accomplishments in community development. On Friday, April 18, 1975, Walnut Grove Auction Sales hosted the “Raymond Weathers Dairy Cattle Dispersal”—and just like that he was retired at age 53.

I run it by myself to 1975. I run that dairy to put them kids to college. When I got them out of college, bye bye cows.

When he sold the herd, there were 86 cows and 120 acres. After the dairy, he rotated the fields between wheat and soybeans.

Plant wheat in October, cut the wheat in May and June. Then plant soybeans. If I had a 1,000 acres of land that’s all I would do, oats and wheat, next year change it. Followed by soybeans. Two crops a year.

He retired from the dairy business 15 years before I was born. The granddad I knew had the same forearm and hands, but he used them to till, plow, plant, harvest— and love. He was always working, even though it was not for money— I look back and realize he was always working to prepare food for his family and neighbors, but to him it was not work. His garden was massive for someone in his 70s and then 80s—he grew a lot of peanuts, sweet potatoes, green beans, watermelon, and pumpkins. He used to say, “I don’t care if it makes anything, I just like to see it grow.” He had fig bushes at the dairy and he would sit at the kitchen table and peel figs for hours; often this is when I would write while he passed along history through the art of storytelling.

There’s a common thread from my grandparents food journey to mine: a 74- year old organization called South Carolina Farm Bureau. South Carolina Farm Bureau describes itself as a grassroots, non-profit organization celebrating and supporting family farmers, locally-grown food, and our rural lands through legislative advocacy, education, and community outreach. The first record of my grandparents paying Farm Bureau membership dues is scribbled in a 1959 Farm Record Book. The date was October 30, 1959; the annual dues were $8. My grandparents were Farm Bureau members for at least 54 years, if not longer.

As a member of Farm Bureau, I feel more connected to my food roots than anywhere else. Farm Bureau is a place where people still remember my grandparents, still remember Bowman as the Dairy Capital of South Carolina, and still remember when their next of kin was the ultimate source for growing and harvesting the food that fed their family and their neighbor.

The general country store on Duncan Chapel Road is a rundown shanty that is barely standing. Goods have not been traded there for years. Pappy Paul and Mammy Ressie’s house and dairy are no longer standing; it is an empty field with no sign of the life gone by. The Bowman Young Farmer Chapter is no longer active, but the South Carolina Young Farmer and Agribusiness Association, as it is called today, exists in some towns and on a state level. My grandparents are no longer living, but they left me with so much including my namesake—Ashley Weathers— my wedding band that belonged to Granddad before I wore it, Granddad’s Farmall 140 tractor, and a rich agricultural heritage.

Today, I work on Main Street in the Central Business District of Greenville. My food journey comes in the form of chocolates, fudge, and ice cream in a retail store called Kilwins. While it is a lot different than dirt roads and silage and milking parlors, there is still a lot that’s the same. One important lesson my granddad taught: you can’t be a truck farmer. “You can’t ride around in the truck and watch, you have to get out and help, get your hands dirty,” he would say. When I was a kid and he would say this, it went right over my head, but after five years as a business owner, I can relate now more than ever.