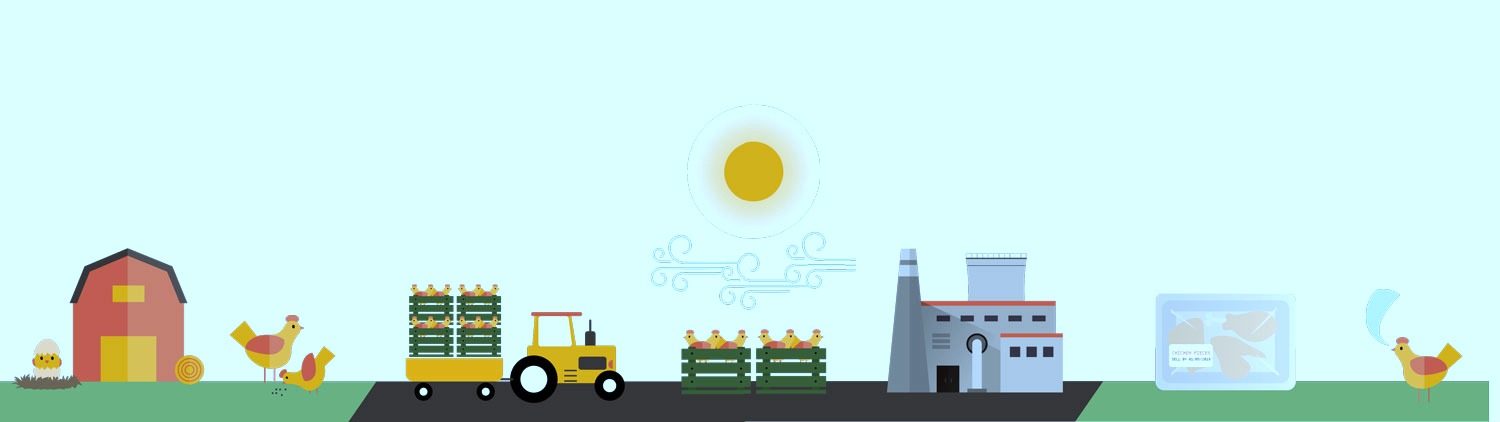

The Problem with Processing

Upstate poultry processors find themselves in a lose-lose bind without enough money to go around.

Last year, a little over a week before Thanksgiving, Gail Cooley from Patient Wait Farms headed up I-85 toward the poultry processing plant in Marion, NC, with a trailer full of pre-sold heritage turkeys in tow. When she rolled up to the facility to keep the appointment she had made at the beginning of summer, she found the business closed. A call to the owners of the Foothills Pilot Plant revealed that they had shut the plant down entirely in October. They hadn’t notified their customers because they thought everyone would either see media coverage of the closing or hear about it from fellow farmers.

At that point, Williamsburg Packing in Kingstree, SC, the only other USDA-certified poultry processor for small-scale producers in the Carolinas, was booked until January.

Patient Wait’s customers were counting on local heritage turkeys for their holiday tables, and the farmers needed to recoup their large upfront investment in the birds; turkeys are pastured and fed for 6 months before the farmer sees any revenue. Fortunately, fellow Upstate farmers sprang into action, bringing together the help and equipment necessary to get the turkeys processed and on their way to customers.

Foothills also was the processor of choice for Agnew Hopkins of Timberock at Hopkins Farm. Marion was the closest plant to his location and offered the option of bringing home fresh, rather than frozen, turkeys. Fortunately, Agnew heard about the closing and had just enough time to arrange to take his turkeys to Kingstree. Although he was sure to have his Thanksgiving turkeys back in time for customers, the change in facility nearly doubled the length of the trip he’d have to make, biting into his slim profit margin. And unlike Marion, Kingstree did not offer same-day pickup, so he’d have to make two 370-mile round trips to bring his Thanksgiving turkeys home.

This story had an all-too-familiar ring to it. In 2015, during a farm tour in the Raleigh- Durham area, one of our host farms shared a dilemma. Their regular poultry plant had just closed, less than two weeks before their next appointment, and they’d have to take their chickens to a processor nearly 200 miles away. The facility? Foothills Pilot Plant. That change would affect their process, schedule, and cost structure— if they could even get an appointment in time.

Foothills’ closing had an impact far beyond North and South Carolina, though; they served hundreds of producers. Even the Chicago Tribune picked up the story, noting that the closure put “farmers in six states in a bind” for the holidays.

While explaining the details of being undercapitalized, the owners of the facility addressed the entire economic conundrum. Poultry farmers struggle to make a profit, so processors are reluctant to increase their prices. At the same time, the facilities have to ensure that their own slaughterhouse workers are fairly compensated. If prices are too low, they can’t pay their own employees fairly. Skilled workers will leave. If prices are too high, farmers won’t be able to stay in business.

To help mitigate the effects of the closure, Carolina Farm Stewardship Association (CFSA) secured temporary exemptions in North Carolina for farmers experienced in processing to handle other farms’ birds. (Currently, farmers can process up to 1,000 birds on-farm without special facilities, as long as the poultry is sold to end users.) CFSA also collected information about mobile processing units available for rent and identified a mobile processing unit in South Carolina that was able to perform on-farm slaughter and processing: Goat Daddy’s Farm Ltd. in Elgin.

Not surprisingly, even with CFSA’s efforts to relieve the processing bottleneck, the facility in Kingstree and similar facilities in Kentucky have not been able to absorb the remainder of Foothills’ customers.

Locally, Fosters Meats in Duncan is in the process of making adjustments to their facility and adding equipment to meet requirements for USDA poultry processing certification. They anticipate being able to accept chickens within the next few months but will only process them one day a week. While their facility provides a much-needed service, South Carolina will still need more processors to meet demand.

Steve Ellis of Bethel Trails Farm plans to build infrastructure that will allow him to process up to 5,000 chickens, ducks, and turkeys that he raises each year with the help of farming partner Noah Tassie. Ultimately, the move won’t reduce the cost of processing, but it will bring the processing schedule and quality of finished product under their control. It also allows the birds to be handled in a more humane way. Taking them off -farm for processing requires that they ride hundreds of miles to the processor, where they may sit on the docks for hours, often in blazing heat or freezing cold.

Although we unquestionably need more poultry processing facilities to work with small-scale farms, that element is only one part of a larger economic problem that local farmers face. High-quality food that is produced sustainably, which entails paying a living wage to the people who are growing and raising that food, simply costs more. The cheap food we often buy may be grown in unknown conditions by people who live in squalid situations and are paid less than minimum wage. Are we willing to pay that premium? And if not, what does that mean for the future of farming?

For more information on poultry processing in the Carolinas, see “Options for Poultry Processing” at www.carolinafarmstewards.org.

The Cost of Your Dinner Bird

ORIGINAL INVESTMENT: $3 - $5 per bird

This is the average price for chicks or ducklings from hatcheries with safe practices.

FEEDING: $2.50 per bird

Pastured birds are feed for 16 weeks with good quality feed (with no GMOs) ordered in bulk for $17.75/50 lb.bag.

TRAVEL: $1.37 per bird at Foothills/$2.50 per bird at Kingstree

Farmers must make two round trips to either Foothills or Kingstree for drop off and pick up.

LOSS: 20% of total

For 200 birds, farmers can expect to lose as many as 60 prior to processing.

PROCESSING: $8 per bird at Foothills/$4.35 per chicken and $10 per duck at Kingstree

All fees are for whole birds. Farmers who want them cut into pleces incur additional charges.

SALE: $25 average per duck/$20 average per chicken

Meat ducks come in around 4 pounds dressed weight and are sold at $6-7/Ib for duck, $5-7/Ib.for chicken

FARMER PROFIT: $3-8 per bird not including labor

The total investment for each bird is around $17-18

These numbers do not include...

Advertising maintaining a website, water, electricity (to keep chicks warm in the beginning) or anything at all for the farmer’s time.