Wisdom of the Woods

In the South Carolina wilderness, one writer learns self-reliance can mean more than just mere survival.

Through the hardwood bottoms of north Georgia, a boy follows his great grandfather. In the woods of South Carolina’s Piedmont, he runs ahead of his uncle or his father. Here, Joshua Barnes feels safe, more at home than he is anywhere else. The men he is with carry the wisdom of generations: from the mountains of North Carolina, on down to the Piedmont and into Georgia, passed from father to son to son, from hunter to sharecropper to farmer, these people know how to read nature. They understand how to scout, to hunt, to fish. They know plants offer nourishment, which of their lookalikes pose a threat. If they need to, they can forage for natural tinder, ignite fires in rain. A knife and their own understanding are enough to make a feast. These woods sustain them, body and soul.

Those boyhood days drift away as Joshua enters adulthood, choosing a career in law enforcement first, and then as an executive assistant to the mayor of Williamston. He builds a successful life. Underneath it all, though, something is missing. By the time he meets Janna, whom he marries, he is more than ready for a change—not a move forward, but back: to the woods and the wisdom he still carries from those generations who came before him. It’s not just a personal return he wants, though. Barnes wants to give back. He wants to revive the dying traditions that nourished him—body, mind, and spirit— in his youth. He wants to offer it to a new generation, to make it live again. He wants to help people become more self reliant, to know that they have all they need, not just to survive, but to live well.

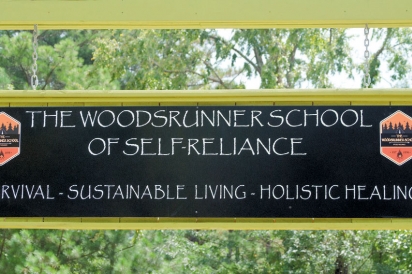

Though he never thought of himself as a teacher, he finds himself called to start a school. When he suggests this to Janna, she’s all in. Though she has a full-time job that isn’t related to the woods in any way, she’s also trained in Sustainable Agriculture and Holistic Practices. Like Joshua, she wants to help people nourish their whole selves. This is how the Woodsrunner School of Self Reliance begins in 2016, driven by this notion of self-development and sustainability.

Ten minutes off I-26, but seeming as though it’s in the wilderness—it’s across the street from the Enoree Ranger District of the Sumter National Forest, and fifty yards from the Palmetto Trail—the Woodsrunner School is not the boot-camp style of school that some may associate with ‘survival.’ Classes at the school range from wild edibles to navigation to firecraft to sustainable living. On any given weekend, you might find a gathering of bushcrafters, or a fresh group of students taking an Introduction to the Wilderness Class.

Students, so far, have been as varied as the course titles, from age five to seventy-something, and from experienced hunters and fishers to people who are taking a walk in the woods for the first time. There are plans for a sizeable group of Girl Scouts to arrive in the fall.

Whatever the class, a sense of community is key.

“When students learn,” Joshua says. “It’s a community effort. They have to work together.”

Joshua and Janna have been amazed at the level of support the school has received in its first year: donations of land to use, and students who come for a class and then return to help, forming what Joshua calls the Woodsrunner family.

Several members of the family gather even when there aren’t scheduled classes, to help out, or, perhaps to build a fire and prepare a feast over it. No pots and pans. No campstove. A stand of bamboo provides skewers for kebabs, and a pot for boiling water or cooking grain.

“Who thinks about using grass to boil water?” Joshua asks, as he notches a wide piece of bamboo, cutting out a rectangle that will serve as a lid. Water and grain fill the hollow between the two solid ends that naturally occur along each stalk of the plant. “You have to be able to improvise.”

Propped against the edge of the fire, the bamboo gathers enough heat to cook the food within. The water keeps it cool enough to prevent ignition.

Cut and cleaned branches form a spit to which meat is tied. Joshua sets about cooking fish en papillote, using kudzu leaves foraged from the woods nearby as the envelope. Neatly tied with the stem of the kudzu, the tidy envelopes go right into the ashes.

The cooking takes time, but no one’s in a hurry. The ‘family’ gathers by the fire—a couple from North Carolina who have been living off the grid for the past three years, neighbors of the school, former students. They sip tea made from wild plants: yarrow, clover, St. John’s Wort, lemon balm, mountain mint.

The meat is turned on the spit, kebabs flipped. Below them, the fish steam in their parcels. Sweet potatoes cook in the coals. All told, it takes around three hours from the start of the fire to the feast. Off the spit, out of the coals and into mouths. The fish, unwrapped from their envelopes, steam, moist and tender. The kudzu-leaf envelope is edible, too.

As the meal comes to an end, the group is beyond full. Far from mere survival, this is living well. Joshua, Janna and their Woodsrunner family demonstrate how to use what’s around them to find nourishment for body, mind and spirit.

To find out more about the Woodsrunner School of Self Reliance, go to thewoodsrunnerschool.com or find them on Facebook