Past, Present, Future

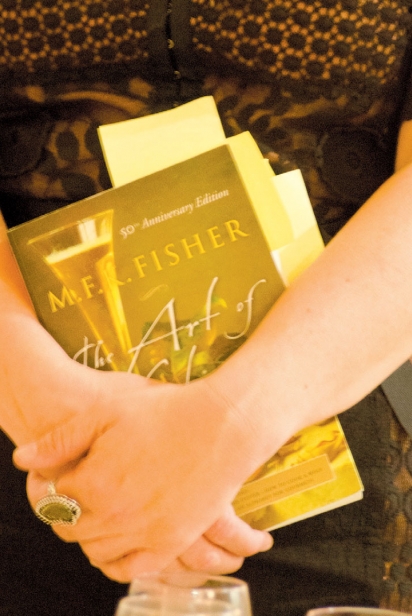

MFK Fisher, Mother Of Modern Food Writing

When Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher began writing her first collection of culinary essays, she had just returned from France to the Southern California of her youth. Only not exactly. She returned in the midst of the Great Depression, to job lines and bread lines and hungry children in her father’s orange groves. She returned as a young wife for whom the bloom of the honeymoon had worn away, and she returned having been changed by everything she’d learned to eat and drink while she’d been living in Dijon. Arguably the belly of France, Dijon was still rising up from the economic ravages of World War I, but food there was celebrated, particular, and passionately representative of its place. This tension in Fisher’s life, between lushness and lack, illustrated the principles that would mark her work forever. In short, and in 1937, she wrote about how what we eat is who we are.

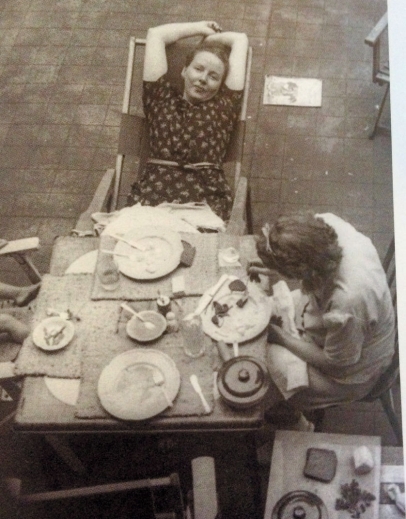

And in Serve It Forth, that first collection, she wrote beautifully, about food and farmers and restaurants, specific meals both present and past. She wrote about what we eat as children and how it shapes us. She wrote about the perfection of a potato “baked and pinched open and bulging with a mealy snowiness,” the value of honest bread, honest wine, the value of simplicity. She was drawn to the old culinary books in the Los Angeles Public Library, the heft and smell of them, the brittle pages in her hands, their recipes for Roman fermented fish sauce and tales of ancient feasts. She wove these histories through episodes from her own gastronomic education, as a child at her strict grandmother’s table, and as a wide-eyed young wife in the markets of Les Halles. She imagined her ideal kitchen, her ideal dinner party, a meal that could make someone fall in or out of love with her. She understood the power of her personal story, seen through the universal lens of food.

Some 80 years later, this is the range and foundation of every edible magazine across the country.

I came to Fisher as a food writer long before I came to be the editor of edible Upcountry, fell in love the way you do when you’re young, diving in headlong. I read everything she’d published. I began to imagine the sort of woman she must have been from her confident voice on the page, her insistence, her beautiful sentences full of exclamation points and adverbs and all the things you’re supposed to use with extreme caution as a writer if you use them at all. I began to try to understand her perspective on food, and the pleasures of the table. And so, in part because of her, coming into the fold of edible magazines felt very much like coming home.

In the foreword to The Gastronomical Me, Fisher addresses the power of her subject head on. People ask her why she writes about food rather than weighty subjects like struggle, love, and security. She says, “It seems to me that our three basic needs, for food and security and love, are so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot straightly think of one without the others. So it happens that when I write of hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it, and warmth and the love of it and the hunger for it. . . and then the warmth and richness and fine reality of hunger satisfied. . . and it is all one.”

We feed ourselves every day, our whole lives through, and in so many different ways. I often wonder why MFK Fisher is not more of a household name, but then I have immersed myself in her work, spent years in study and appreciation. I’ve forgotten what it’s like to have that first true sounding of recognition, that spark.

I know it’s something we are all hungry for.

The Arrangement

MFK Fisher's early life and career are the fact behind the fiction in Ashley Warlick's new novel, The Arrangement. Set against the backdrop of Depression-era Hollywood and Europe between the wars, this book gives us a young woman's perspective on the pleasures of the table, as seen through her blossoming writing career, her passionate entanglements, and her own love of a good meal. Here's an excerpt from the first chapter, a little taste of what it's all about:

The waiter brought her trout under glass. He prized the flesh away from the spine in efficient sheets, pink and curling, though Mary Frances well knew how to use a knife; it was what a waiter did for a woman, what a woman allowed in a restaurant like this. Tim's face, cocked against his fingers; this had become fun or funny, she wasn't sure which, his eyes sweetly blue and blank as a baby's. After the fish, there was quail en papillote, the parchment broken and billowing the scent of dry grass, and her mouth became slick with fat and the second glass of wine. She forgot about Al and Gigi and what would be said about this evening later, and she ate.

If she understood art, if she could write, if she was beautiful and smart and a tangle of other things still taking shape, what she was truly good at was this. She ate slowly, she sat back from her plate, she allowed her pleasure to show on her face. And she was wining, always, to try the next thing.